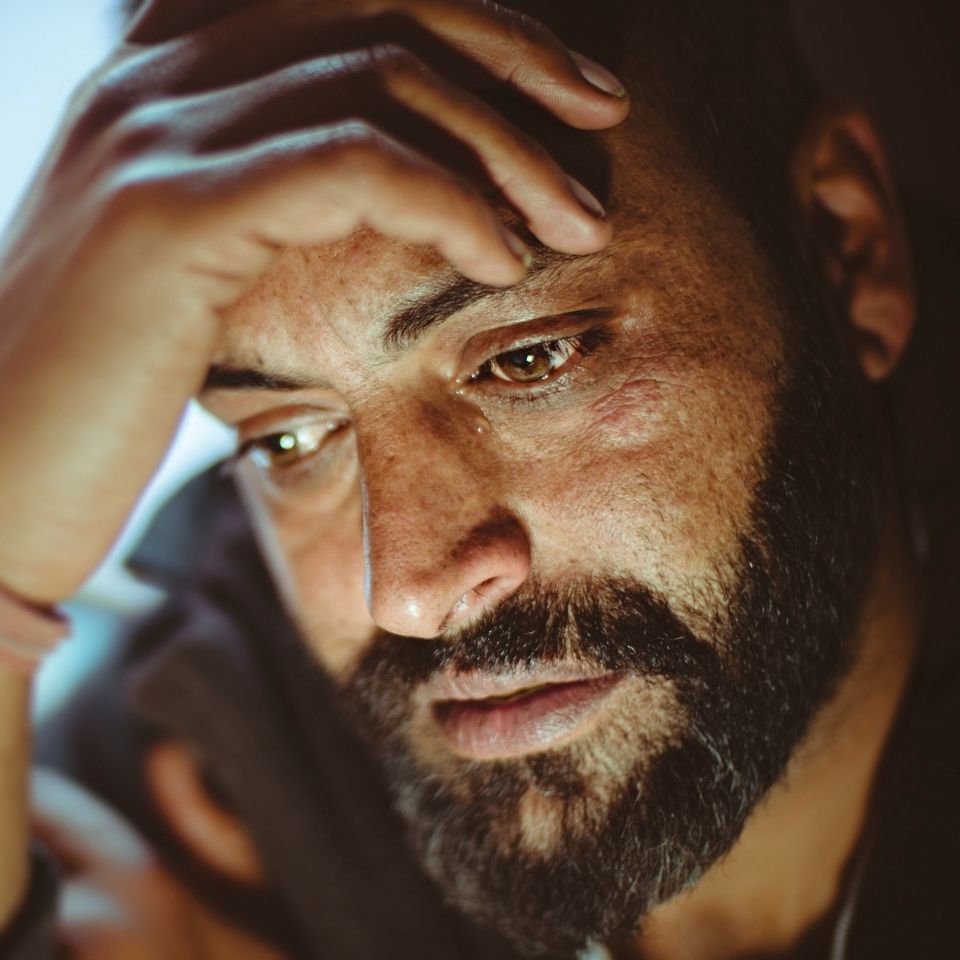

Schizophrenia is a debilitating mental disorder that encompasses a range of cognitive, behavioral, and emotional symptoms

Understanding symptoms and potential risk factors can help prompt the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia. Read the article below to learn more about schizophrenia and its underlying pathophysiology

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental disorder that belongs to a spectrum of psychotic disorders. It is characterized by a distorted perception of reality and changes in behavior, which impair functions necessary for daily living and can be disabling.1

Epidemiology

It is estimated that schizophrenia affects 1% of the world’s population,2 and is slightly more prevalent in men than in women (1.4:1).3 In the United States, schizophrenia prevalence is between 0.6% and 1.9%,4 equating to more than 3.2 million individuals.5 Peak symptom onset typically occurs in men in their early to mid-20s. In women, onset of symptoms occurs later in life: in their late 20s, and after the age of 44, the latter defined as late-onset schizophrenia.6,7 Though late-onset schizophrenia accounts for approximately 15% to 20% of all schizophrenia cases,7 women are overrepresented, making up 66% to 87% of patients with onset after the age of 40 to 50.6

Symptoms of schizophrenia

Symptoms vary considerably from patient to patient, but generally fall into four categories: positive, negative, cognitive, and mood.1

Positive symptoms involve distortion of thinking and perception, and include hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia.8 Hallucinations commonly affect auditory perception, but may occur in any of the senses;1 often, the person will hear accusatory or threatening comments.1 Positive symptoms frequently mark the onset of schizophrenia, particularly in adolescents and young adults.1

Negative symptoms involve decline or loss of normal functions.1 The person may show a lack of motivation (abulia), inability to experience pleasure (anhedonia), lack of initiative (avolition), or reduced interest in social activities.1 These symptoms are often transitory. However, understanding their underlying cause is important as they may be a consequence of other extrinsic factors such as environmental deprivation, neuroleptic treatment, or depression.1

Cognitive deficits affect the normal thought process and can vary in severity. Symptoms include deficits in attention, executive function, speed of processing, and verbal learning and memory.1,8

Mood symptoms include affective experience impairment, depression, and anxiety.1,8 Some people with schizophrenia show increased emotional arousal and reactivity (emotional paradox), while most people present with depressive symptoms at different stages of the illness, which contribute considerably to the disease burden.1 A number of clinical assessment scales have been developed to measure each of these symptoms, e.g., Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),9 Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS),10 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),11 and Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS).12

Pathophysiology

The manifestations of schizophrenia have been attributed to structural deficits and functional changes in the cerebral cortex, particularly the prefrontal and temporal lobe regions.13,14 However, imaging has shown that volume reductions and abnormalities in brain matter occur across many brain regions, and these changes may be progressive in the early stages of disease.13,14

In addition, schizophrenia has been linked to major neurotransmitter pathways, leading to several hypotheses regarding its pathophysiology.

The dopamine hypothesis states that aberrant dopamine signaling underlies schizophrenia. The mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways, two of the brain’s major dopaminergic systems, have been implicated in the development of positive and negative symptoms.15,16 They project from the ventral tegmental area and transport dopamine to the limbic structures (mesolimbic pathway) and cerebral cortex (mesocortical pathway).4 Increased dopamine production, decreased dopamine catabolism, and overactive D2 receptors are proposed to lead to hyperactivation of the mesolimbic pathway that results in positive symptoms.15 Decreased D1 receptor activation and imbalances between D1 and D2 receptors in the prefrontal cortex, and decreased activity of the caudate nucleus are proposed to cause hypoactivation of the mesocortical pathway that results in negative symptoms and cognitive deficits.15,16

The glutamate hypothesis is based on the ability of glutamate to directly and indirectly modulate dopamine release via dopaminergic neurons and GABA interneurons.15,16 Hypofunctional NMDA receptors in both the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways can produce positive and negative symptoms, respectively.15,16

The serotonin hypothesis is, like the glutamate hypothesis, based on modulation of dopamine. Serotonin can modulate the release of dopamine, GABA, and glutamate, and hyperactivation of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor is known to affect the mesolimbic pathway.17

Diagnosis

As there are currently no diagnostic tests available, diagnosis of schizophrenia can be a long and challenging process.18 The DSM-5 criteria include the presence of at least two of the following:19

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Disorganized speech

- Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

- Negative symptoms (at least one of which must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech)

In addition, patients must present with the above criteria for a significant part of one month.19 The level of function of a major area must be markedly below that at onset, and disturbances must persist for at least six months.19 Other disorders and causes must be ruled out and special considerations are made for people with certain previously diagnosed disorders.19

Progression of schizophrenia

Functional impairment begins in the prodromal phase and is followed by acute exacerbations in the progressive phase, where remission and relapse occur with symptoms fluctuating in severity.1 Continued remission with residual symptoms and relapses follows in the chronic/residual phase.1

Risk factors

The inherent heterogeneity of schizophrenia has led to a lack of consensus regarding diagnostic criteria, etiology, and pathophysiology. However, it is generally accepted that schizophrenia is a result of a combination of genetic, developmental, environmental, and social factors.4,14,20

Genetic risk factors. The estimated 79% heritability of schizophrenia indicates a substantial genetic risk.21 Studies have shown that an individual’s risk of illness if their parents have schizophrenia is approximately 40%.4 Monozygotic twins have an even higher risk, with 48% developing schizophrenia if the other twin has it.4 Genome-wide association studies have identified more than 100 different single nucleotide polymorphisms leading to glutamatergic dysfunction and abnormalities of dopamine signaling, which may explain some of the cognitive symptoms observed in schizophrenia.14

Developmental risk factors. These can be divided into prenatal and perinatal factors. Maternal stress, bleeding, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, nutritional deficiencies, maternal infections, and intrauterine growth retardation may affect fetal neurodevelopment during pregnancy. 4,14,20 Obstetric complications that could be linked to the development of schizophrenia include emergency cesarean section, asphyxia, low birth weight, use of forceps, as well as birth in late winter or early spring.4,14,20

Environmental and social risk factors. There are a number of environmental or social factors that may affect a person’s neurodevelopment, and, thus, cause the onset of schizophrenia.14,20 Growing up and/or living in urban or densely populated environments has been frequently linked to increased risk of schizophrenia or psychosis in general.20 A history of head injury,14 epilepsy,14 autoimmune disorders,14 substance abuse,20 discrimination,3 or childhood adversity3,20 are other important factors. However, some of these environmental exposures are also associated with other neurodevelopmental outcomes such as autism, epilepsy, and ADHD; therefore, caution must be made when making a diagnosis based on these factors.14

Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. Schizophr Res 2009;110:1–23.

Biagi E, Capuzzi E, Colmegna F, et al. Adv Ther 2017;34:1036–1048.

Khan RS, Machens A, Basa J, et al. Nat Rev Primers 2015;1:15076.

Patel KR, Cherian J, Gohil K, et al. P T 2014;39:638–645.

Lu C, Jin D, Palmer N, et al. Transl Psychiatry 2022;12:154.

Li R, Ma X, Wang G, et al. J Transl Neurosci (Beijing) 2016;1:37–42.

Folsom DP, Lebowitz BD, Lindamer LA, et al. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2006;8:45–52.

Millan MJ, Andrieux A, Bartzokis G, et al. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016;15:485–515.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261–276.

Kring AM, Gur RE, Blanchard JJ, et al. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:165–172.

Overall JE, Gorham DR. Psychol Rep 1962;10:799–812.

Addington D, Addington J, Atkinson M. Schizophr Res 1996;19:205–212.

Kalsgodt KH, Sun D, Cannon TD. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2010;19:226–231.

Owen M, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Lancet 2016;388:86–97.

Schwartz TL, Sachdeva S, Stahl SM. Front Pharmacol 2012;3:195.

Brisch R, Saniotis A, Wolf R, et al. Front Psychiatr 2014;5:47.

Stahl SM. CNS Spectrums 2018;23:187–191.

Davidson J, O’Gorman A, Brennan L, et al. Schizophr Res 2018;195:32–50.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2016. Table 3.22, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Schizophrenia Comparison. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519704/table/ch3.t22/. Accessed April 22, 2022.

Stilo SA, Murray RM. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019;21:100.

Hilker R, Helenius D, Fagerlund B, et al. Biol Psychiatry 2018;83:492–498.